Вавада Казино: регистрация на официальном сайте

Казино Vavada online заработало в 2017 году. Сегодня это одна из самых популярных площадок, которая предлагает массу развлечений на любой вкус. Клуб имеет официальную регистрацию, выданную правительством Кюрасао. Работает честно и прозрачно, о чем говорят отзывы пользователей. Имеет право предоставлять услуги онлайн-гемблинга по всем направлениям. Софт, размещенный на платформе, также лицензирован и выпущен ведущими разработчиками. Характеризуется высоким процентом отдачи и работой без прокруток.

| 💎 Бренд | Vavada |

| 💎 Официальный сайт | |

| 💎 Рабочее зеркало |

Актуальное зеркало - перейти на зеркало |

| 💎 Платформы | iOS, Android, Windows |

| 💎 Количество игр | 3600+ |

| 💎 Языки | RU, EN |

| 💎 Саппорт | Live-чат, контактный телефон, skype, email |

| 💎 Мин. депозит | 50 RUB |

| 💎 Мин. вывод | 1000 RUB |

Официальный сайт Vavada, как и личный кабинет, имеет русскоязычный интерфейс. Поддерживается работа на других языках. Площадка отличается современным дизайном и простотой использования. Функционирует более 5000 игровых автоматов, действуют live-игры, постоянно проводятся турниры с большим призовым фондом.

Вавада лояльно относится ко всем клиентам, позволяет играть не только на деньги, но и бесплатно. Многие видеослоты поддерживают демонстрационные версии, в которых сессии проводятся на очки. Регистрация потребуется только для платных ставок. Подтверждать личность не обязательно, если гемблер не планирует выводить крупные выигрыши и не занимается мошенничеством. Пользователям предоставляются бонусные поощрения и другие подарки, которые увеличивают шансы на успех. Действует программа лояльности. Повышение статуса открывает игрокам новые возможности.

Для решения проблем работает техническая поддержка. Операторы быстро отвечают на вопросы и помогают всем игрокам, вне зависимости от статуса. Пополнение счета и снятие денег возможно разными способами, в том числе банковскими картами. Транзакции надежно защищены современными технологиями.

Зеркало Vavada

Зеркала - копии виртуальных игорных заведений, которые содержат аналогичный функционал. Дубликаты создаются по следующим причинам:

- Конкуренция со стороны других казино - игорные платформы стараются заполнить выдачу ссылками на свои источники.

- Блокировка основных ресурсов - игорный бизнес находится под запертом во многих странах. Местные провайдеры блокируют площадки по требованию властей. Дубликаты помогают обойти ограничения.

- Тестирование новых игр - любые технические работы нарушают функционирование портала. Зеркала позволяют бесперебойно пользоваться всеми слотами и другими развлечениями.

- Распределение нагрузки - наличие большого количества посетителей негативно влияет на сервер. Дубликаты эффективно решают эту проблему.

Зеркала Вавада задействуются для бесперебойного входа на сайт. Они дублируют весь софт, бонусные поощрения и привилегии. Копии также обновляются, через них легко пополнять счет и снимать выигрыши. Уровень безопасности аналогичный, как и на основном ресурсе. Ссылки на зеркала регулярно публикуются в Телеграм-канале и группах сервиса в ВК. Предоставляются сотрудниками техподдержки по запросу.

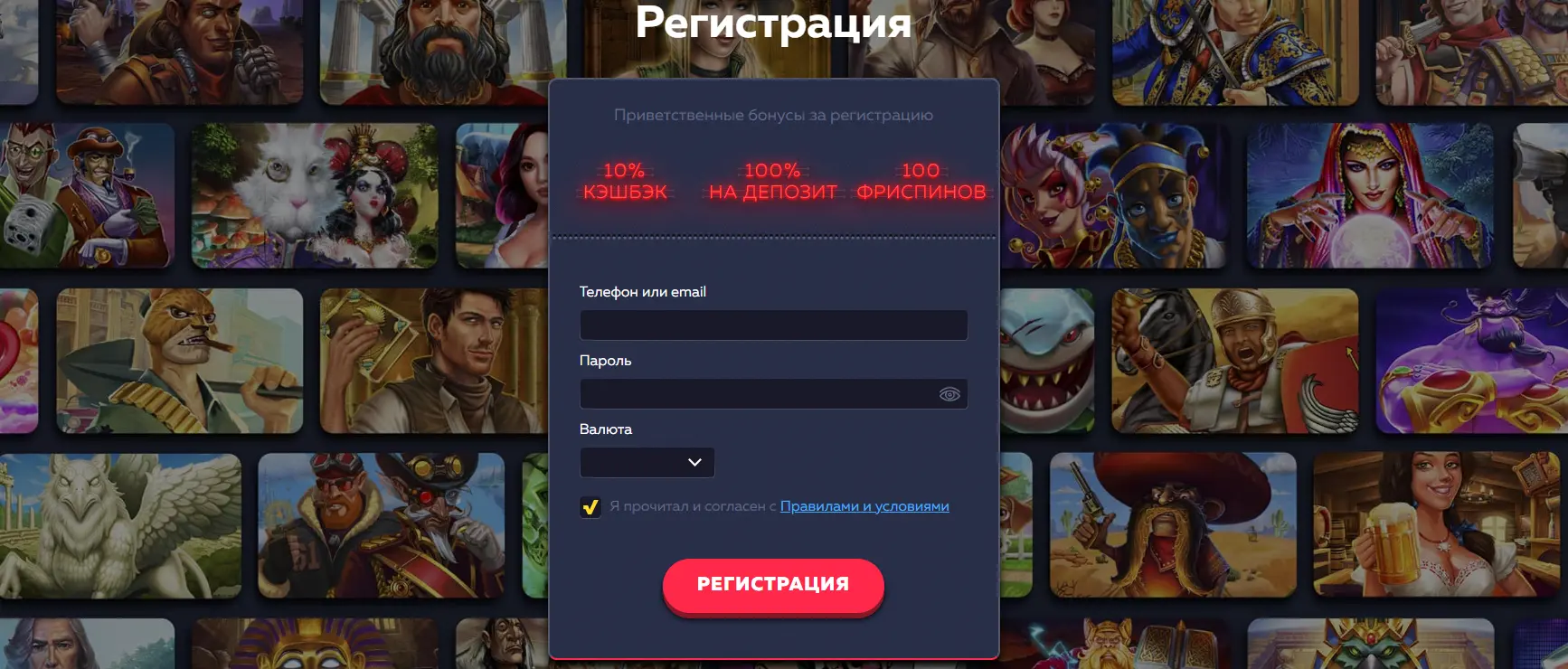

Регистрация в казино Вавада

Учетная запись нужна для платных сессий и пользования всеми возможностями сервиса. Регистрация быстрая, чтобы ее пройти посетителю необходимо нажать на одноименную иконку в шапке окна, указать номер телефона, почту и пароль, а также согласиться с правилами клуба. Первый вход в личный кабинет Вавада после регистрации осуществляется автоматически. Здесь можно менять контактную информацию, вносить депозиты на баланс, создавать заявки на вывод денег, активировать бонусы, получать уведомления и т.д.

Верификация обязательная при снятии больших выигрышей. Подтвердить личность может потребовать администрация Вавада. Например, для определения возраста или при подозрении в мошенничестве. Для прохождения процедуры следует загрузить сканы страниц паспорта с фото или другого документа, который подтверждает личность. Проверка занимает 1-3 дня. По завершении клиенту восстанавливается доступ к функционалу или его аккаунт блокируется.

Бонусы Vavada

Различные поощрения используют практически все онлайн-казино. Для игорных площадок это возможность привлечь новых геймеров. Постоянные клиенты получают более высокие шансы на успех, могут ставить с минимальным риском проиграть. Бонусы существуют разные. Подарки, которые начисляются после пополнения счета, называются депозитными. Поощрения, предоставляемые за совершение полезных действий - бездепозитными. В клубе действует несколько видов бонусов.

Приветственный бонус Вавада за регистрацию

Первый приз игрок получает сразу после создания аккаунта в виде 100 фриспинов для автомата Great Pigsby Megaways с вейджером отыгрыша х20. Симулятор посвящен богемным свинкам. Характеризуется классическим геймплеем, отличной дисперсией и заносом в х20000. На барабанах предусмотрены дикие и другие спецсимволы. Процент отдачи - 96,08%. После первого депозита внесенная сумма на счет удваивается. Ее можно использовать на любых видеослотах.

Промокоды Vavada на сегодня

Купоны выдаются платформой постоянно. Они открывают бесплатные вращения на определенных симуляторах, содержат множители депозитов, фишки для столов и многое другое. Получить промокоды Вавада сегодня можно у операторов чата за совершение определенных действий. Коды публикуются на проектах партнеров сервиса, каналах блоггеров, которые освещают сферу азартных развлечений и в сообществах онлайн-казино в соцсетях.

Кэшбэк

Возврат части денег, потраченных на площадке, осуществляется ежемесячно. Величина кэшбэка - 10% от израсходованной суммы. Выдается поощрение при условии, что гемблер потратил больше, чем заработал.

Программа лояльности Vavada сейчас

Активность игроков на сервисе позволяет повышать статус. Всего их шесть:

- Новичок - ставится после регистрации. Открывает доступ ко всем развлечениям. Возможен вывод до 1000 долларов в сутки раз и до 10000 в месяц.

- Игрок - активируется при ставках от 15 долл. Работают обычные турниры и снятие до 10000 долл. в месяц.

- Бронзовый - получают все геймеры, которые потратили более 250 долларов в течение месяца. Вывод возрастает до 15 тыс., активируется доступ к бронзовым состязаниям. При пополнении баланса задействуются более весомые множители.

- Серебряный - устанавливается для всех, кто потратил на ставках более 4000 долл. в мес. Размер обналичивания - 20000 долларов. Допускается участие в крупных турнирах.

- Золотой - для получения необходимо потратить в течение месяца 8 тыс. долл. Клиент получает все привилегии клуба. Сумма вывода увеличивается до 30 тыс. долл. Становятся активными любые состязания, кроме платиновых.

- Платиновый - высший статус, который устанавливается, если платные ставки превысили 40000 долларов Можно выводить до 100000 долл. и участвовать в любых состязаниях. За геймером закрепляется личный менеджер.

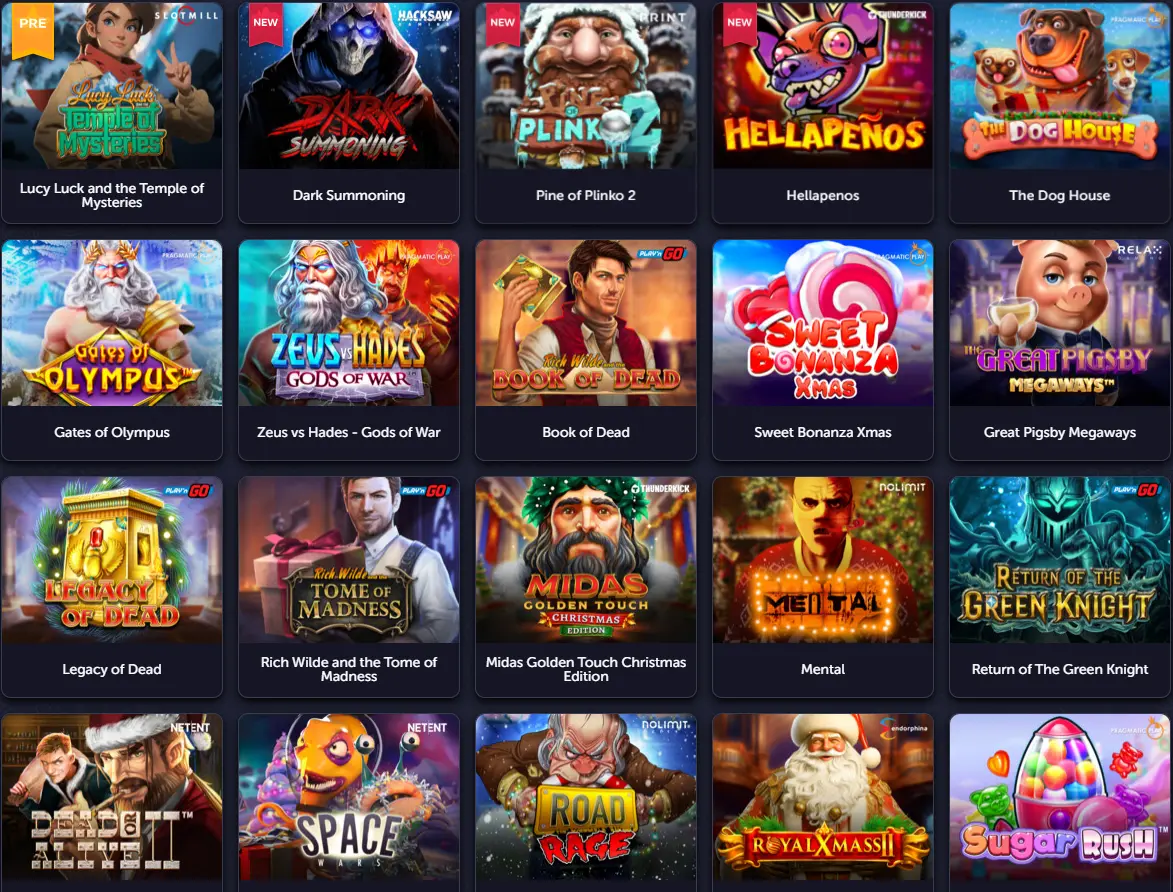

Игры Вавада

На сайте более 5 тыс. автоматов. Софт лицензирован, процент отдачи - от 95%. На каждом симуляторе есть шансы выиграть джекпот. На выбор пользователей широкий ассортимент классических автоматов, которые ранее использовались в реальных клубах. Есть новые видеослоты с современной графикой, качественной анимацией и музыкальным сопровождением. Для удобства поиска софт Vavada live разбит на несколько разделов.

Самая большая и популярная группа - слоты. Представленные симуляторы отличаются простыми правилами и хорошими шансами на победу. Многие поддерживают демо-режимы. Один из новейших онлай-автоматов - Magic Piggy с ретро-стилем, полем 5х5 и 19 линиями выплат. Выигрышные символы - карты от десятки до туза, премиальные вишни, подковы, лимоны и бриллианты. Процент отдачи - 96,5%. Еще один популярный вариант - Book of Dead с тематикой Древнего Египта. Крупные выигрыши обеспечат спецсимволы и множественные призовые комбинации. Сессии ведутся на 5 барабанах с 10 активными линиями выплат.

В столах Вавада представлены настольные развлечения - покер, рулетка, блэкджек и баккара. Есть и другие симуляторы. Например, захватывающая онлайн-игра - Aviator. Здесь нет классических барабанов, но предусмотрен солидный выигрышный потенциал. Ставки гемблеров умножаются на большие коэффициенты. Уже первый спин дает множитель. Он постоянно растет, позволяя, при определенном везении, получить крупное вознаграждение. Видеослот Plinko основан на принципе падающих шаров. Посетителю необходимо угадать, в какое отверстие провалится игровой атрибут, делая ставки на деньги или очки.

В разделе лайв Vavada.com состязания транслируются в режиме реального времени. Пользователям доступны карты и другие развлечения, в которых принимают участие реальные крупье и дилеры. Правила также простые. Например, в рулетке Lightning Roulette все основано на удаче и везении. В покере нужно собрать комбинацию выше, чем у дилера. Камеры, которые размещены в каждой студии, помогают пользователям следить за всеми картами на столе.

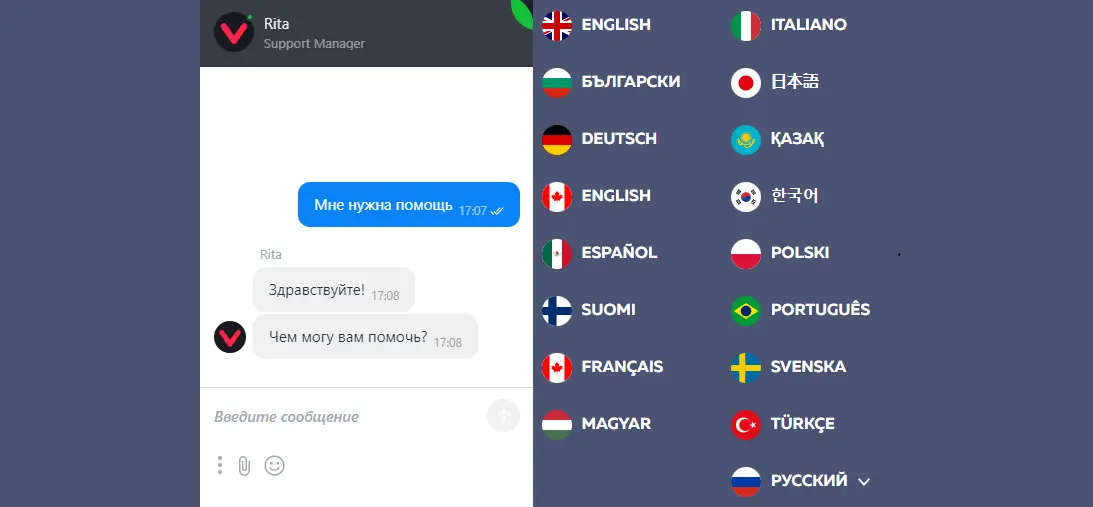

Поддержка Вавада

Сервис помощи работает круглосуточно. Связываться с сотрудниками можно через чат или по электронной почте. Гемблеры, как правило, обращаются с такими вопросами:

- способы создания учетной записи и вход в ЛК;

- условия участия в онлайн-турнирах;

- блокировка личного кабинета, утеря логина или пароля;

- правила прохождения верификации;

- порядок отыгрыша бонусных поощрений;

- информация об акциях и планируемых мероприятиях.

Специалисты техподдержки реагируют быстро. Время ответа на вопросы не превышает нескольких минут.

Партнерская программа Vavada

Чтобы стать партнером нужно зарегистрироваться и связаться с менеджером через чат, который ответит на вопросы и предоставит необходимую информацию. Партнерка Вавада привлекает внимание регулярными выплатами. Действуют две модели оплаты:

- RevShare - начисляется до 50% от суммы, потраченной привлеченными игроками;

- CPA - оплачивается суммарный депозит от активного гемблера в течение 20 дней после создания учетной записи.

Продукт поддерживает работу с 8 валютами и разные варианты оплаты. Постбек предоставляется по понедельникам за предыдущие 7 дней.

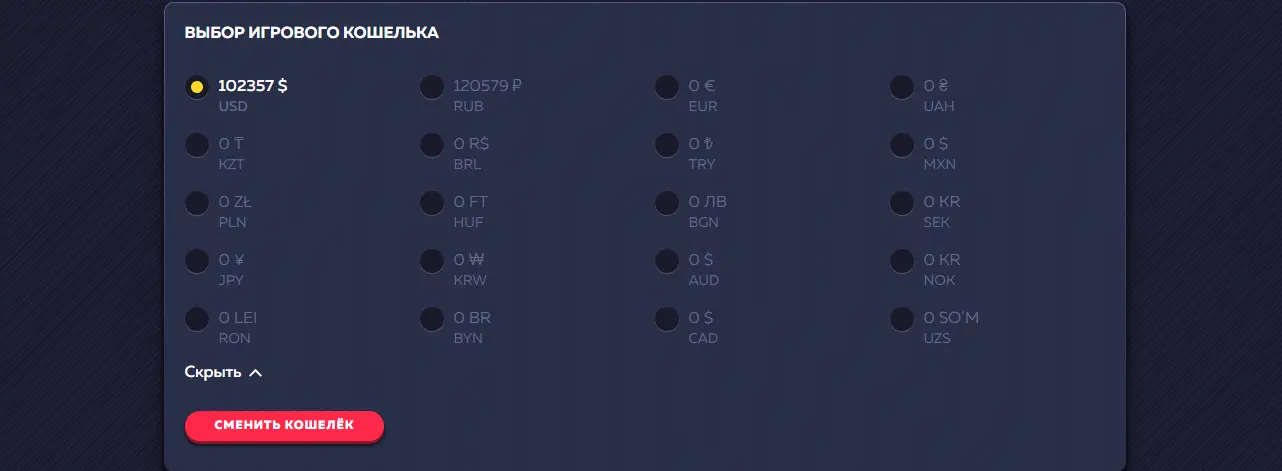

Способы пополнения и вывода денег в casino Vavada

Транзакции возможны в 22 валютах с помощью карт, кошельков WebMoney, Monetix, Piastrix, платежных систем Skrill, Neteller, Rapid Transfer, криптовалютных бирж и т.д.

Для пополнения баланса необходимо нажать на иконку в шапке страницы, найти раздел «кошелек» в ЛК и нажать на «пополнить счет». В новом окне откроется список вариантов оплаты. Следует выбрать подходящий и написать сумму. Комиссии со стороны ресурса не взимаются.

Вывод с Вавада осуществляется через одноименную функцию. Для этого нужно создать заявку в ЛК, указать способ выполнения операции и сумму, затем отправить в обработку.

При снятии выигрышей важно учитывать, что:

- минимальная сумма - 1000 р.;

- обналичивание осуществляется через аналогичный сервис, что и при внесении на баланс;

- время транзакции от 1 часа до суток - администрация быстро обрабатывает заявки, задержки изредка случаются со стороны платежных сервисов.

В Ваваде действуют лимиты на снятие выигрышей в сутки, неделю и месяц, которые зависят от текущего статуса. Чем он выше, тем больше выплаты.